Ju Jiandong: China Should Consider a Progressive Carbon Tax

Professor Ju Jiandong is the Unigroup Chair Professor at the PBC School of Finance of Tsinghua University, Director of the Green Finance Development Research Center at the Tsinghua University National Institute of Finance, and a researcher at ACCEPT. The following is an abridged translation of his speech at the 2021 Tsinghua PBCSF Economic Forum on Carbon Neutrality, held on September 16, 2021. This translation was originally published in the Pekingnology newsletter on October 20, 2021. The piece was translated by Alexander Wang, copyedited by Zhixin Wan, and reviewed by Zichen Wang, the founder of Pekingnology. It is reposted here with permission.

Today, I will mainly talk about two tools: the carbon market and the carbon tax.

The carbon market is the most discussed topic now. My point of view is that it is very difficult to achieve carbon neutrality only by relying on the support of the carbon market. China has piloted the carbon market in eight provinces and cities since 2013, and the national carbon market has started to operate in July 2021, which is still immature.

At present, China's carbon quota is distributed free of charge, with a quota of 4 billion tons, exceeding the European Union's 2 billion tons. It is worth further discussion on whether the carbon quota should be distributed free of charge or auctioned when it comes to the optimization of resource allocation.

At present, the carbon trading in China's carbon market is only spot trading, without extensive participation of financial institutions and effective price discovery tools such as futures, options, forwards, and swaps.

However, the EU carbon market is rich in financial products and active in futures trading. From the perspective of liquidity, the liquidity of China's carbon market is very low. The turnover rate of China's carbon market is about 5%, while that of the EU is 400%, which is 80 times that of China.

From the perspective of the carbon price, China's carbon price is about 50 RMB per ton, while the EU's carbon price is 50 euros per ton, which is about 7.6 times that of China. Therefore, to develop and improve the carbon market, greater progress should be made in the legislation (total emission reduction, quota issuance method), quantification, pricing, and other aspects.

In addition, referring to the development of other domestic factor markets, such as the capital market, futures market, intellectual property market, and even the football market, development hasn’t been a smooth ride.

The carbon market is a brand-new market with [unclear], and there will be many difficulties in its development. Therefore, it will be a very long process to establish a well-developed carbon market and it’s likely that it will be an imperfect market for many years like other factor markets. I think it will be very difficult to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 with the sole support of the carbon market.

If the carbon market (alone) can't make it, there are other administrative practices, such as switching off electricity and withdrawing the loans from coal producers, which would do great harm to the enterprises and the economy. Another common and mature practice in the world is the carbon tax.

I think we can take a progressive carbon tax into consideration.

First of all, it is necessary to clarify what “green” means. My definition is to calculate the average of carbon density in different industries, and those with carbon emissions below the value can be defined as green, while above can be defined as non-green, which shall be punished.

For example, suppose that the average value of the power generation industry’s carbon density is 600g/kWh, then enterprises emitting carbon less than the average value can be defined as green. Suppose that the average value of the carbon density in the transportation industry is 100g/km, then the enterprises’ average carbon emissions less than 100g/km can be defined as green. Suppose that the average consumption of residents is 10 tons per person each year, then carbon emissions from one resident’s consumption below 10 tons per person each year can be defined as green.

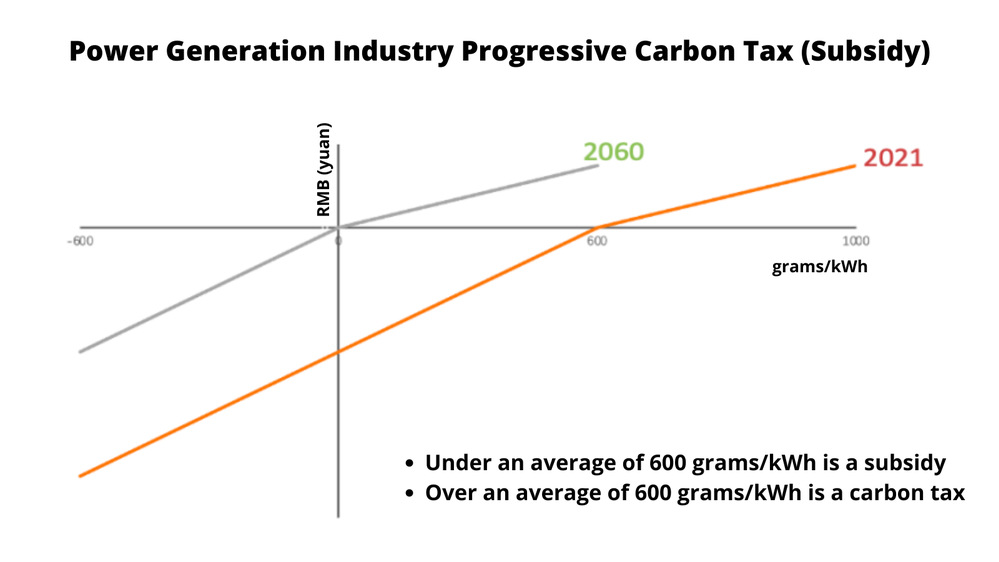

Taking the power generation industry as an example, the horizontal axis is carbon emission intensity (grams/kWh), and the vertical axis is RMB (yuan).

The curve indicates the size of the carbon tax (subsidy) levied on enterprises with different carbon emission densities, and the slope of this curve shall change, that is, the higher the carbon emission density, the greater the tax rate.

From 2021 to 2060, this carbon tax (subsidy) curve will continue to move left [from the orange to the gray], that is, the average carbon emissions will change from 600g/kWh in 2021 to 0g/kWh in 2060. Enterprises with a carbon emission density below the average of 600g/kWh can be subsidized, and the carbon tax can be levied on those above 600g/kWh.

At present, in the power generation industry, the carbon emission density of coal-fired power must be higher than the average, while that of natural gas power generation may be slightly lower than coal-fired power, and the carbon emission density of photovoltaic and other clean energy is even lower.

By punishing coal-fired power with high carbon emissions and subsidizing low-carbon power generation such as those on clean energy, enterprises can choose their own combination: reduce thermal power generation, increase solar power generation and hydropower generation, and get subsidies as long as their carbon emissions are below the average value.

Take the carbon tax (subsidy) of residents' consumption as an example, which would relate to income distribution. Let us suppose that the average carbon emissions from residents' consumption is 10 tons per person each year, and one who emits over 10 tons every year will be taxed, one who emits below 10 tons subsidized. Carbon emissions from residents' consumption come from driving, building houses, running a private jet if you are rich, etc.

From the perspective of residents' consumption, it is obvious that the rich produce more carbon emissions and the poor produce less. Therefore, the rich should pay more carbon taxes, while the poor bear less tax burden. Individuals can also reduce their carbon emissions by planting trees. By 2060, the average carbon emissions will be 0, the average should be zero—realizing carbon neutrality in residents’ consumption.

The first advantage of taking the average value for each industry is that through this improved carbon tax method, it is easy to get the support of the enterprises. Half of them will support it because they are below the average value, and the other half may oppose it because they are above the average value.

Another advantage is that it is flexible to set different average values in different industries, and the setting of the average value could also be flexible, which makes it easy to gain support from relevant parties and get policies passed.

Unlike some current practices, if we take strict administrative transformation measures against the whole industry, the whole coal-fired power industry and the whole power-generation industry may oppose.

In addition, in countries with strong administrative implementation capabilities like China, it is more effective to adopt a carbon tax than to rely on the carbon market.

Based on the analysis above, we have put forward a specific economic path to achieve carbon neutrality, which is to promote the continuous decline and circulative iteration of the average carbon emissions of various industries through a progressive carbon tax, so as to achieve carbon neutrality in 2060.