Eric Maskin: Why We Need Government and Economics

At the Third Annual Conference of Government and Economics, held on May 22, 2021 at Tsinghua University, audience members viewed a virtual lecture from Eric S. Maskin introducing the new field of government and economics. What follows is a transcript of his lecture that has been lightly edited for clarity. Eric S. Maskin is a 2007 Nobel Laureate in Economics, the Adams University Professor at Harvard University, and Co-President of SAGE.

Hello everyone, it's a pleasure to be able to participate once again in this important conference. Today, I'd like to talk about some work that I've done with David Daokui Li.

This work explains why we think government and economics deserves to be considered as its own field of study.

What I plan to do in this brief talk is first to argue—and I don't think this is going to take too much argument—that government has been a major player in all highly developed market economies, and furthermore, it has been critical to the success and economic performance of these economies. Then, I want to briefly review other fields within economics that examine the connection between governments and the economy. Finally, I'll come back to the main point, which is that Daokui and I feel that there needs to be a new field combining government and economics. This is the reason, in particular, why we have launched the new journal.

The Expanded Role of Government

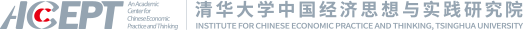

As for the idea that government has been a major economic player, if you go back to the 18th century, Adam Smith’s time, at that point government played a relatively small role in economic matters. One way of looking at the evolution of government's role over time is in this chart.

This chart only goes back to the 1870s, which is well after the time of Adam Smith. We see that at that point, among today's OECD countries, government was occupying somewhere between 5 and 20 % of these countries’ GDP. If we look at current economic circumstances, we see that up to 60 % of GDP is now occupied by government. So, it's been quite a dramatic change over these 150 years. We would get the same results if we looked at employment, assets, and so on.

But not only have governments expanded in their fraction of GDP—they have also expanded in scope. For example, in the 18th century, much of national defense was provided by hired military forces. Now, the military is run by the government. So, instead of hiring foreign mercenaries, members of the military are essentially government employees.

Equally important, since the 19th century, we've seen an enormous expansion of what we would call social welfare programs. These include social security—guaranteed income after retirement—and national health programs that protect people when their health fails. The government is also heavily involved in protecting the environment and providing infrastructure such as roads, internet, and of course, public education. Public education was created in the 19th century, and it's essentially universal, at least in highly developed countries today.

Another important area in which government has expanded is the area of market regulation. By this, I mean government intervention to make sure that markets produce the outcomes that they're supposed to produce.

Now, there are various explanations for why government has expanded so dramatically. One point, which I will be emphasizing in a moment, is that if a country wishes to develop its economy from a fairly primitive level to a highly developed state, the government is crucial for that trajectory. But even after economies become highly developed, there's a strong argument that since modern economies are so complicated, government still needs to become involved. This is not only for regulation, but also in the area of providing public goods such as public education, the subsidization of scientific research, and so on.

In contemporary times, another major concern has been inequality. In many highly developed countries, we see a dramatic increase in the gap between rich and poor. Government seems to be the only actor who can address this rising inequality and do something to stop it.

Case Studies of Government Involvement in Economic Growth

Now let me review the history of a few countries that have seen dramatic increases in the role of government. First, let’s look at the United States in the second half of the 19th century. In the mid-19th century, the United States was not a particularly distinguished economy in the world, but by 1900 it had clearly become an economic superpower. The actions of the American government had a lot to do with this.

First, there was extensive investment by the government in infrastructure, particularly the development of railroads. Second, the government was heavily involved in promoting education and making sure that human capital was adequate for a modern economy. This was done through the creation of public schools in addition to land grant universities. The government also had a lot to do with encouraging innovation. Patent law was developed in order to protect innovators from having their discoveries immediately imitated, in which case they would not be able to get a reasonable return on those innovations. We also saw the government playing a large role in the development of new industries.

What the American government typically did was to protect infant industries through high tariffs, shielding them from competition. Then later, once the industries in question became more secure and highly developed, the tariffs would be reduced. This had the benefit of sharpening the industry and improving it through competition. It also enabled the American economy to expand to trade with other countries.

It turns out that a similar pattern of government intervention was seen in Germany, and also in Japan in the latter half of the 19th century. However, South Korea is a somewhat different story because its growth was a 20th-century phenomenon.

Only since the Korean War in the 1950s did we begin to see the South Korean economy begin to take off, but when it did take off, the involvement of the government was essential to its success. What the Korean government did was to identify particular industrial sectors it would support, then pour enormous resources into those sectors. They built the South Korean economy through an export policy. That is, the sectors that they supported helped build the economy through international exports. And that, of course, was the same policy that proved to be so successful in China.

Now, China is a latecomer compared to the other countries as discussed. Its reforms didn't begin until the late 1970s, but it more than made up for lost time by sustaining unprecedented expansion for many years. We saw growth rates of well over 10 percent, and this had a lot to do with government involvement, which promoted new enterprises and helped transform land use from agricultural purposes to industrial purposes. The government also got involved in expanding and deepening financial markets. Finally, the critical ingredient in China’s success was the willingness to borrow ideas, technologies, and best practices from countries that had already been successful. China was able to catch up so quickly because it didn't have to reinvent everything itself—it was able to borrow.

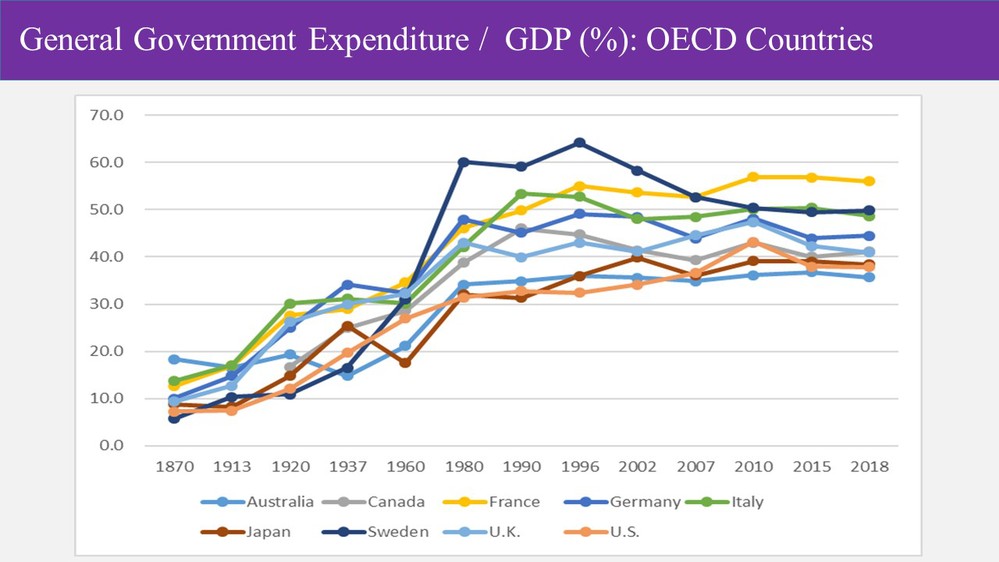

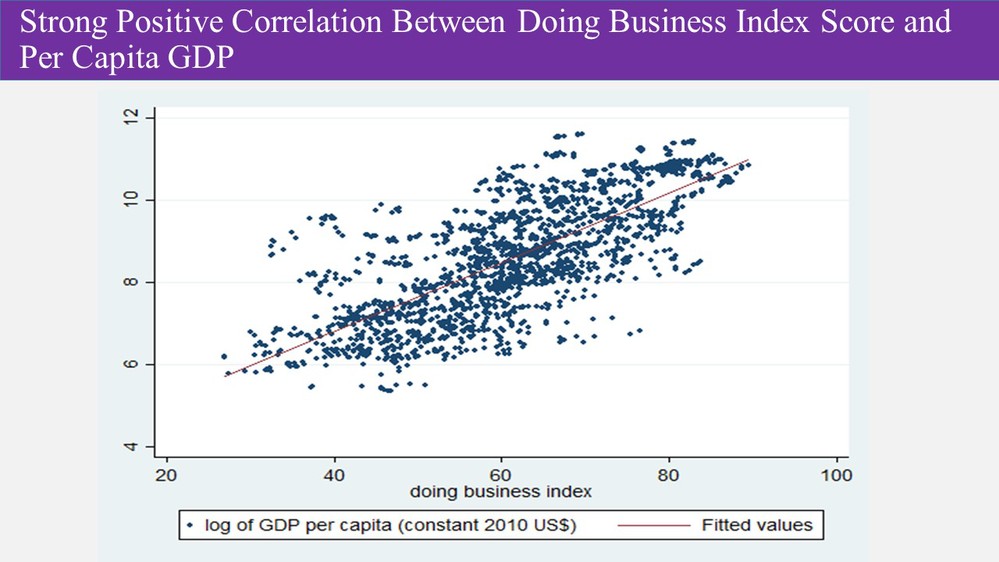

Now, a major point that I'm trying to get across is the idea that the success of the economy is closely related to the success of the government, and this can be measured through statistical evidence. If we look at GDP versus the World Bank’s Doing Business Index (and the Doing Business Index has a lot to do with government involvement), we see a strong, positive correlation between how easy it is to do business—that is, to what extent does government promote easy business—and per capita GDP. We also see, according to World Bank indices, that political stability is strongly correlated with GDP, as is the quality of regulation and the strength of the rule of law. All of these are dependent on government.

The Need for Government and Economics

Now, you might ask, why do we need a new journal on government and economics? After all, there are existing fields with their own journals that have examined the connection between governments and markets. Let me talk about some of those fields for a couple of minutes, but then argue there are things that these other fields leave out.

Take public economics, for example. Public economics is the study of taxation by the government to raise money for social insurance and public goods. One critical ingredient of most work in public economics is the idea that government is in the business of trying to maximize social welfare. So, most of the research in public economics assumes a benign government that is simply trying to maximize some index of social welfare, and the reason for the government's involvement is that there is some kind of market failure. Public goods are an example of that—public goods can't be provided through the private market, so they have to be provided by governments. Or, there is a need to redistribute income because of the need for social insurance, or because of inequality. However, public economics fails to examine the problem that government itself may have its own agenda—an agenda distinct from maximizing social welfare. Therefore, we think that public economics makes an important contribution to the topic of government and economics, but an incomplete one.

Second, there is the field of public choice. This is a field that was pioneered and developed by people such as James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock. Now, public choice theorists do look at the agenda of people and governments. However, unlike public economists, they largely ignore the effects that government may be having on public goods or income distribution. So, both public economics and public choice have gaps that need to be filled.

Then there's the field of industrial organization, which looks at the behavior of industrial companies. Of course, government plays a role in industrial organization. If there is non-competitive behavior—for example, if industries are monopolized or are oligopolistic—government may interfere and impose anti-trust remedies. Or, in markets where there are important externalities, a government may have to interfere to correct those externalities through regulation. But again, as in public economics, the focus of governments in industrial organization is on correcting market failures.

Then there's the field of political economy, which these days is sometimes called political economics. If we were to go back to the nineteenth century and use the term political economy, then we would be referring to economics in its totality. But by the beginning of the twentieth century, we saw the separation of economics and political science, and that separation continued until late into the twentieth century, when we saw a reawakening of interest in how political interactions may affect economic outcomes. So, within political economics, we see much work on how elections, voting, or political lobbying may affect the real economy. What we don't often see is a study of why the government needs to be involved so heavily in the economy, as was the case in the US, Germany, and Japan in the nineteenth century. So, that's where I think this new field of government and economics may be filling an important gap.

We want a field in which government is not just correcting market failures, as in public economics, but is participating actively in markets, because that's actually what we have seen historically. So because government has clearly become such a crucial player in essentially every market economy, we want to understand, first, what is behind government actions, what are the incentives leading to particular government behaviors, and how do those government behaviors end up affecting the economy? That is the overall agenda of this new field, and it leads to a variety of interesting research questions.

For example, in industrial organization, we would want to understand how governments affect the process of entry and exit into markets. We know that government can certainly encourage entry through tax breaks and subsidizing lands. We also know that governments can encourage or interfere with exit. There is a famous concept from János Kornai known as soft budget constraint, in which the government starts giving supplementary funding to an enterprise and then finds it very difficult to stop. This is an example in which the government may interfere with efficient exits. This fits within the subject matter of the new field that we are proposing.

In the area of market developments, we want to understand more deeply why government had to participate so thoroughly in developing the American, German, and Japanese economies in the 19th century, and the Chinese economy in the 20th century.

There are also macroeconomic issues worth examining. Of course, governments around the world are interested in managing business cycles—macroeconomic fluctuations—but their approaches have been very different. Some emphasize the supply side. This was the approach, for example, of the Thatcher and Reagan governments in the 1980s. Others—and this goes back to Keynes—concentrate on the demand side. If we are in a recession, you try to stimulate demand to get us out of that recession. An approach that economists such as Milton Friedman have promoted is to have governments stay out of the fiscal domain and intervene in the monetary or financial domain—have the federal reserve adjust interest rates to manage macroeconomic fluctuations. There is clearly much to do to understand what combination of these three approaches has proved to be most successful.

In many countries around the world, we see that not just private agents, but also governments, own significant productive assets. This is true in market economies. In every market economy, the government owns significant productive assets. Why is this the case? What is the cause for the government to be involved in this way, and what are the consequences of governments’ involvement in the ownership of productive assets?

A very important issue these days, in my own country, is why has government failed? Why has the American government failed, over a generation, to provide adequate infrastructure? Or to put it another way, why has the infrastructure that was once there been allowed to deteriorate so badly? And another question for the whole world, why have we failed to act to protect the environment? The most notable incidence of this failure is how we have allowed climate change to not only progress, but to accelerate. This is clearly a failure of government, and we would like to understand how this failure came about.

In addition to all of these positive questions, there are basic normative issues as well. If we could choose the optimal size of government, what would it be? What is the right presence of government in GDP figures? And a related question: in what sectors of the economy should the government be interfering? What is the proper scope of the government? Given that governments are intervening, what is optimal policy? All of these are deep and important questions from the normative side.

I hope that, in the last few minutes, I’ve been persuasive in communicating the two points that: 1) governments have played—and will presumably continue to play—a critical role in every modern economy, and 2) the interactions between government and economy deserve their own field, with wider and deeper attention, which is again the reason we have created this new journal. I personally very much look forward to seeing how this emerging field will develop. Thank you very much!