ACCEPT Report: The "Southbound Shift" of China's Economy and Population Has Been Occurring for 1,500 Years

Originally published by 21 Economics on December 28, 2020, translated by ACCEPT.

Author: Xia Xutian

Source: https://m.21jingji.com/article/20201228/herald/92fe80cef2497cc5cbae25b8337b2624.html

China’s geographical population distribution currently lags behind the country’s productivity layout. Reconfiguration of China’s economic geography will become a new growth point for the country’s economic development in the medium- and long-term.

On the afternoon of December 27, the Academic Center for Chinese Economic Practice and Thinking (ACCEPT) and the Center for China in the World Economy (CCWE) jointly held the Tsinghua University Forum of China and the World Economy. The two research centers also used this occasion to release a report which shows the significant and profound changes in China’s population distribution over the past 15 centuries. Since the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, China’s productivity has been continuously shifting southward. China’s population distribution has also followed this pattern, gradually transitioning from a layout in which the north outweighs the south into one in which the south outweighs the north.

According to the report, China’s geographical population distribution currently lags behind the country’s productivity layout. This is demonstrated by the fact that the combined GDPs of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen account for 12.5% of China’s total GDP, whereas the combined populations of the four cities only make up 5.2% of China’s entire population. Judging from the share of national GDP and population held by China’s top 10 and top 20 cities, it appears that the population proportions of these cities lag behind their GDP proportions at a rate of 11% and 16%, respectively. Reconfiguration of China’s economic geography will become a new growth point for the country’s economic development in the medium- and long-term.

The “southbound shift” of China’s economy and population has been occurring for 1,500 years.

At the aforementioned forum, Lu Lin, an ACCEPT researcher within the Tsinghua University School of Economics and Management, pointed out in her presentation of the report that from a long-term perspective, it is inevitable for a country’s geographical population distribution to shift to meet the historical requirements of productivity growth. This development process is irreversible.

Lu Lin explained that ancient China’s economic growth was based on agriculture, and following changes in climate and agricultural technologies, the population of ancient China began to shift southward, changing from a layout in which the north outweighs the south into one in which the south outweighs the north. Since the beginning of the modern era, with the acceleration of industrialization and urbanization, this historical process has never stopped.

According to the report, since the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, the Yangtze River basin in southern China has become increasingly developed and has experienced significant progress in the renovation of water conservancy facilities and rice planting technologies. Thanks to these improvements, the economy in the area south of the Yangtze River has developed rapidly, and China’s economic center has gradually shifted from the Yellow River basin to the region south of the Yangtze River. This “southbound shift” of China’s economic center began during the Wei, Jin, and the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, continued its development in the Sui and Tang Dynasties, became established after the mid-Tang Dynasty, and was finally completed during the Song Dynasty. Correspondingly, the Yangtze River Delta and the regions of Hubei and Hunan have become the most densely populated areas in China.

The report argues that this southward migration trend has continued into the modern era and has accelerated since reform and opening up. This is because the growth miracle of more than 40 years of reform and opening up has had an even more dramatic impact on the geographic distribution of China's population.

Based on the historical GDP database of Oxford-Tsinghua-Peking University, the report provides analysis from the perspective of productivity growth. Calculated in absolute value (GDP is set as 100 in the year 1840), the average annual growth rate was about 0.24 from the years 980 to 1840. During these 860 years, total GDP increased by a factor of 7.93. By comparison, in the over 40 years since the reform and opening up, China’s economy has grown by a factor of 39.29 according to data from the WDI database.

Judging from the magnitude of changes in China’s geographical population distribution, Chinese society is no longer constrained by transportation, language, information, cultural, and legal barriers as in ancient times. The Chinese population now has greater space and momentum for population movement than it did over the previous 1,500 years of history.

In her presentation, Lu Lin outlined the following changes to the geographical distribution of China’s population since 2010:

· First, China’s demographic center has shifted from core megacities to regionalized central city clusters, especially in the Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta, and Chengdu-Chongqing regions.

· Second, the urban-rural population flow has started to shift toward regional migration rather than cross-regional migration, especially in eastern China.

Such trends result not only from the changes occurring in the geographical population distribution due to increases in productivity and development in industrial and city clusters, but are also a manifestation of the effectiveness of domestic labor factor market reform.

Population distribution still lags behind productivity layout.

According to the report, judging from the current degree of synchroneity between China’s geographic population distribution and the productivity layout, changes in China’s demographic distribution are relatively lagging. Therefore, labor mobility has the ability to unleash huge growth potential in the future.

Take Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen as an example. The combined GDP of these four cities accounts for 12.5% of China’s total GDP, whereas their combined populations only account for 5.2% of China’s entire population. Judging from the share of national GDP and population in China’s top 10 and top 20 cities, it appears that the population proportions of these cities lag behind their GDP proportions at a rate of 11% and 16%, respectively. In another example, we can consider the 10 provinces and cities with a per capita GDP of over 70,000 yuan in 2019. The GDP of these regions accounts for 54.5% of China’s total GDP, whereas their populations only account for 38.1% of the entire Chinese population.

Table 43. Current Distribution of China’s Population and GDP in Certain Provinces and Cities

Cities & Provinces | Total GDP (1 billion RMB) | Total Population (1 million people) | Proportion of GDP within National GDP | Proportion of Population within National Population |

Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen | 12,408.10 | 73.88 | 12.5% | 5.2% |

Top 10 Cities | 23,031.00 | 171.74 | 23.2% | 12.1% |

Top 20 Cities | 34,350.00 | 257.12 | 34.7% | 18.0% |

Top 10 Provinces (and Cities) | 54,017.90 | 543.01 | 54.5% | 38.1% |

Note: “Top 10 Cities” refers to the ten cities that rank highest in terms of total GDP, which include: Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Chongqing, Suzhou, Chengdu, Wuhan, Hangzhou, and Tianjin. “Top 20 Cities” refers to the twenty cities that rank highest in terms of total GDP, which include the aforementioned 10 cities and Nanjing, Changsha, Ningbo, Wuxi, Qingdao, Zhengzhou, Foshan, Quanzhou, Dongguan, and Jinan. “Top 10 Provinces (and Cities)” refers to the ten cities/provinces that rank highest in terms of total GDP, which include: Guangdong Province, Jiangsu Province, Shandong Province, Zhejiang Province, Chongqing City, Hubei Province, Beijing City, Shanghai City, Tianjin City, and Fujian Province.

Sources of Data: Provincial Bureaus of Statistics

The report emphasizes that the reconfiguration of China’s economic geography will become a new growth point for the country’s economic development in the medium- and long-term.

The first reason for this is that the reconfiguration of economic geography is, in essence, the reconfiguration of population and labor. The flow of labor from low productivity regions to high productivity regions will increase the marginal output of labor and optimize the combination of labor resources with other factors of production, enhancing production efficiency at the macro level.

Second, the reconfiguration of economic geography will be driven by population movement, which in turn will spur several new infrastructure and urban construction projects, thereby increasing the level of fixed asset investment and creating new objective demand.

Third, through the reconfiguration of economic geography, China will be able to make full use of the Matthew effect and the agglomeration effect of city clusters, promoting the further expansion of China’s economic scale and driving the country’s economic growth rate.

The impetus for the reconfiguration of economic geography comes first from the spontaneous flow of population. Laborers, especially young laborers, have the will to move in order to work and live in regions with higher wage levels as a way to obtain more income, and this laborer shift will also drive laborers’ families to relocate to higher-income regions accordingly. However, at present, the transfer of young laborers in China is not sufficient. Furthermore, the mobility of their families and the choice of living places for middle and high-income people are restricted by household registration and social security regulations. Thus, the spontaneous movement of China’s population has not yet been fully unleashed.

In addition to population movement, capital has an inherent tendency to flow to regions with the highest rates of return. Such regions are often densely populated areas with relatively rapid growth rates, creating a second driving force in the reconfiguration of economic geography.

Unbalanced development exists in numerous regions.

According to the report, most regions in China are currently experiencing unbalanced development, and consequently, their growth potential has not been fully released.

Take Henan, Shandong, Anhui, and Jiangsu Provinces in east-central China as an example. Although these four provinces all ranked high in terms of provincial GDP in 2019, obvious inter-regional income gaps exist within each province. In southern Henan, southwest Shandong, northern Anhui, and northern Jiangsu, local inhabitants have significantly lower income levels than those from other regions in and around their province.

Lu Lin believes that the factors leading to these gaps in economic development include geographic features (predominantly plain terrain), demographic conditions (high population density), resource endowments (relatively limited access to all types of resources), transportation conditions (deficiencies in transportation infrastructure), and cultural differences (belonging to different dialect areas), etc.

Table 46. Regions with Relatively Low Levels of Economic Development

Province | Region |

Henan | Zhumadian, Zhoukou, Shangqiu, Anyang, Xinyang, Puyang, Pingdingshan, etc. |

Shandong | Heze, Linyi, Jining, Zaozhuang, Dezhou, Liaocheng, etc. |

Anhui | Fuyang, Haozhou, Huaibei, Suzhou, Liu’an, Huainan, etc. |

Jiangsu | Xuzhou, Lianyungang, Suqian, Huai’an, Yancheng, etc. |

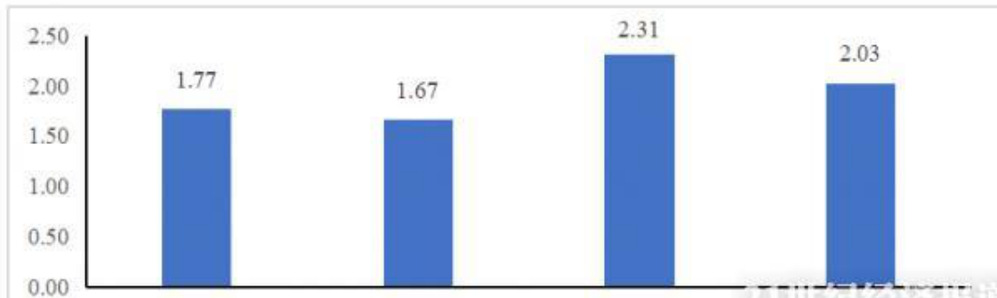

Table 47. Per Capita Income Ratio of the Four Provinces in East-Central China (Other Regions/Lower Income Regions)

Henan Shandong Anhui Jiangsu

The report estimates that if the per capita GDP of the aforementioned underdeveloped regions can be raised to the average level of other regions in the same province, then we will see an increase of the per capita GDP of Henan Province by 24.5%, Shandong Province by 12.5%, Anhui Province by 36.3.%, and Jiangsu Province by 23.7%. If the income gap among the four provinces is eliminated within a decade, then the annual growth rate of China’s per capita GDP will increase by 0.6%.

Further calculations show that—under the assumption that the population structure remains roughly unchanged—if China can achieve the reconfiguration of its economic geography within 15 years (i.e. within three five-year plan periods), and if the ratio of the per capita GDP of the provinces with the highest income to those with the lowest income (excluding municipalities directly under the central government) can be lowered to 1.57 from the current level of 2.6, then China will be able to increase its annual per capita GDP growth rate by 0.9%. Therefore, the report concludes that the reconfiguration of China’s economic geography constitutes a new source of momentum that can help China achieve growth in the medium- and long-term.