Eric Maskin: Mechanism Design for Pandemics

I'd like to speak to you today on a topic, which is both timely about the pandemic, and also I think very relevant for the theme of the conference, which is the interaction between government and the economy. The title is mechanism design for pandemics.

We are all familiar with how well competitive markets work under normal circumstances. Let's imagine that there are many consumers and many producers of some good. If each consumer i gets benefit bi (xi) from consuming quantity xi and each producer incurs a cost cj (yj) from producing a quantity y j ,then the net social benefit from the good is just the sum of the benefits minus the sum of the costs. And for a social optimum, for the economy to achieve an optimum, this of course wants to maximize the net benefit, the sum of the benefits minus the costs subject to feasibility. Feasibility means getting the sum of the consumptions equal to the sum of the supplies. Now, this maximization involves getting a number of things right. You have to get total production right. You have to get each producer j’s production right. And you have to get each consumer i’s consumption right. That sounds as though it might be a complicated thing, but a competitive market solves this through the simple device of prices. So let p be the price of the good that's being bought and sold. Each consumer is going to want to maximize her benefits minus the price that she has to pay for consumption xi, and that means that the first order condition for her maximization equates the marginal benefit and the price. Similarly, each producer is going to want to maximize its net profit which is revenue from selling a quantity yj minus the cost of producing yj , and the first order condition for that is price equals marginal cost. A market outcome achieves the constraint maximum. It achieves the maximization of net benefits, which is sum of the benefits minus cost subject to feasibility.

That’s a simple result, but a very powerful one because it means that in many circumstances we can rely on the market alone for a good allocation. But let's imagine that we're in a pandemic, and there are some goods for which there are no markets because there are some goods that may not even have been created yet. Virus test kits, for example, the corona virus wasn't even heard of a year ago. So when the pandemic struck there was no market for a virus test. Furthermore, some of the most important goods in a pandemic are public goods in the sense that they are created for the benefit of the entire society. They are not created so much for individual consumers. And so if you left it up to ordinary markets to have consumers buy test kits, they might not buy enough because they don't take into account that when they get tested they are also conferring a benefit on the rest of society. Clearly some sort of intervention is needed into the market for virus test kits, and the best candidate for that intervention is from the governments. The government first needs to somehow stimulate production and has to get the right number of those virus tests produced, then it has to get those virus test kits to consumers.

Now, how should the government behave with respect to production? One thing the government could do is simply to order companies to produce some quantity of test kits. A problem with that strategy is that the government doesn't know how much it's going to cost for different companies to produce the kits. And so if it comes up with an arbitrary figure, a hundred thousand test kits, it doesn't know whether that makes sense. There could be other companies that could produce those test kits far more cheaply. Another thing that the government could do is simply set a price that it will pay for each test kit produced and then leave it up to companies to decide how much to produce. But again, if the government doesn't know what different companies’ cost function is, it doesn't really have a good idea of what price to set, doesn't know how much will be produced. And so it may set the price too high or set the price too low.

So some severe informational problems face the governments. But here is where a judicious application of mechanism design can come to the rescue. What I'm going to propose is a variation of a well-known mechanism, the Vickrey-Clarke-Groves mechanism that the government could use in order to get the right quantity of test kits produced.

First the government has to decide what is the benefits of having a total production of the sum of the yj produced. And then as in the model I started with, the government will be interested in maximizing the total gross benefits minus the total cost of production. In other words, the government wants to maximize the net benefit. The problem is that it doesn't know what the costs are, though the costs are known to the producers, but not to the government. So what can the government do? What it can do is to have each firm report its cost function. And when I say report its cost function, I mean, these might be firms which have never produced test kits before. What the government can do is to advertise ahead of time that any firm that wants to produce test kits is welcome to enter as long as it reports its cost function. And then once the government gets all these reports, what it can do is to find production levels for each firm, which maximize the total net benefits, and then it will tell each firm k, you should produce y k*. Now, how does it get firm k to report its true cost function that clearly is critical to this exercise because the government wants to be maximizing the true net benefits. So it has to induce firm k to report its true cost function.

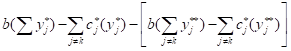

It turns out that there's a simple idea which will indeed get firms to report their true cost functions and it's this. Suppose firm k is paid this expression here. Now there are two parts to this expression.

Then after all of the production is taking place, the government can take these test kits and simply distribute them, either freeof charge or at a low price to citizens. Remember test kits are public goods, so it's important that as many citizens as is feasible to use these test kits. So the government is quite willing and should be willing to subsidize the cost of using the test kits, it will charge at most a low price for the testkits.

Now that the last remaining thing that I have to show you is why if firm k is paid this amount here, it will actually report its true cost function. And the secret is that this parenthetic term doesn't depend at all on firm k’s report. So this parenthetic term will not influence firm k at all. Furthermore, if we look at the first two terms, that's net benefits of society, except for firm k's own cost. So if we take net benefits and we subtract off what firm k will actually have to pay, its true cost, then we have firm k maximizing that social benefits. But if it's maximizing net social benefit, it's going to want to use its actual cost because by using its actual cost in its report, it will be maximizing the true net social benefit. And that's all there is to the argument.

This gets at a key idea in mechanism design, which is to get private agents like firms or consumers to act in a socially responsible way to maximize a social objective. Just give them an objective function which looks like the social objective. This is the social objective that was given to firm k, so naturally, if firm k is presented with this objective, it will maximize that social welfare. This is an idea which could have been used. Sadly, it wasn't used when the pandemic hit the United States. I'm sorry to say that the American response to the pandemic is pretty disgraceful. It was very bad. One reason it was so bad is because the government ignored arguments like this, but there will be other emergencies in the future. And in those future emergencies, I hope that someone will remember mechanism design. It could be very useful in such circumstances. Thank you very much.

【Q & A】

1. When applying this idea to the real world,what would be the key obstacles? Would that be, number one, information obstacles on the part of the government, or the budgetary obstacles? Please clarify.

I think it's very much the former. It's information that the government lacks, and mechanism design is a very good way for the government to acquire the information that it needs to make a reasonable optimization on behalf of the economy. Now it's true that the government is going to run the deficit in this endeavor. It's going to pay firms their marginal contribution, but then it's going to resell their product to consumers at a much lower price. So the government is going to have to make up the difference. That is a reasonable thing for the government to do because after all we are talking about public goods. Public goods have to be funded by the government. You can't expect a public good to be funded through a private market, you will never get enough funding that way. So like any public good, the government has to be the primary funder. So I don't see that as an obstacle because that's true of any public good. It's the informational problem that is the tricky one because we are talking about goods which are not ordinarily produced. We don't know very much about their costs. We don't know. We don't even know which firms might be interested in producing these goods because these are goods that weren't produced last year. So we have to have a mechanism for inducing the firms that are interested in producing to indicate their interest and also to indicate how much it is going to cost them to produce the good.

2. Now, among the informational deficiencies of the government, which part is the most prominent? Would you say that is the benefit function, the benefit of the test kit, or the vaccine? Which is the most difficult to properly estimate for the government? or the other parts?

I think again, it's the costs that are critical. The costs are at least known by somebody. The firms know, presumably know their own costs. The government doesn't know them. So it's an information transmission problem. How do you get these agents who do know the costs to transmit that information to the government? Now the benefit is something which can be obtained by public health people. They can tell you how much it gains from testing a particular population. Consumers are not going to be able to tell you that. In fact, private citizens will have very little idea of what the benefits are because they don't have any experience with the value of the test equipment. Most of them have never taken a virus test in their life. So, the government may not have the information about benefits initially, but it can get that information without a conflict of interest from public health officials.,It’s their job to tell you what the benefit of the test kits are. So it makes sense to rely on them for information on the benefit side. When it comes to cost, there is a conflict of interest because firms in principle have an incentive to pretend that their costs are actually higher than they are. And so how do you overcome that inherent tendency to exaggerate costs?

3. The fact that many governments did not or have not used this kind of mechanism in dealing with the epidemic. And also that… the fact that we economists such as you, including you, already have some ideas on this, right? This is relatively, we already know this. Of course it takes you to highlight this to make this so exciting, right? Now would these facts tell us that we economists have not done good enough job to inform public policymakers, including politicians in dealing with crises like this, so would you say that this is kind of a lack of our efforts, our efficiency in work?

I agree with that. So we economists have two missions, I would say, two responsibilities.

One is to do basic research, on mechanism design for example, and to discover mechanisms such as the one that I was talking about today. But it can’t stop there. Once we have this knowledge, we have to become public spokespeople for the discoveries of economics and communicate these ideas to political decision makers. Because the ideas as interesting as they are will never really be valuable unless they are applied. And that… I have to say that’s one reason why I got interested in our society in the first place because I saw this as a potential vehicle for getting governments interested in what we economists have to say. We have some very valuable things to say, but we have to communicate that effectively to the people who actually set policy.

4. Would you agree that the principle that you proposed to induce the firms to tell truth can be explained by a simple metaphor, simple story? That is often times, when we educate our young kids in order to induce them to act responsibly, we ask our kids to behave as if they are the head of the family. So we somehow hypothetically ask our kids to be in our shoes. If you agree with this metaphor, maybe you want to use your own language to put it there and we can blend in. Would you agree with this metaphor? If you agree, you can ask our kids to share, to see the whole picture, to be like parents?

That’s right.So sometimes kids misbehave, but you tell them if you were parents, let you become parents, then you will behave with more responsibility. I do agree with that metaphor. Of course, in the case of the firms producing the test kits, the reward is more than metaphorical, that is, you don’t have to tell them “imagine that you were the social planner”, you are in fact giving them a payment function which forces them if they are interested in maximizing their profits to behave in the same way the social planner would. So it doesn’t require any imagination on their part whereas in this story of the family and the children, you have to ask your children to do the “thought experiment”, the imaginative experiment of putting themselves in the shoes of their parents.